[00:00:04] Speaker A: ID the Future, a podcast about evolution and intelligent design.

[00:00:12] Speaker B: Welcome to ID the future. I'm your host, Andrew McDermott. Today I conclude my conversation with Dr. John west discussing British writer C. S. Lewis's Prophetic legacy for today regarding science. S. Dr. West is vice president and a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, where he serves as managing director of the Institute's Center for Science and Culture. His current research examines the impact of science and scientism on public policy and culture. Dr. West has written or edited twelve books, including most recently the expanded edition of Darwin Day in America how our politics and culture have been dehumanized in the name of science. The magician's twin c. S. Lewis on science, scientism and society and Walt Disney and live action. Dr. West has also directed and written several documentaries, including two on C. S. Lewis the Magician's Twin, c. S. Lewis in the Case against Scientism and The Magician's Twin, c. S. Lewis and Intelligent Design. In part one, Dr. West unpacks some of Lewis's views on science, and he explains what scientism is the idea that modern science, particularly modern physical science, is the only way that we know truth, that it's our only source of truth about the natural world, about ourselves, about life. We talked about an essay Lewis wrote called Willing Slaves of the Welfare State, including Lewis's views about science progressing without ethics and governments becoming technocracies beholden to the scientists while citizens lose freedom and privacy. Dr. West discussed the COVID pandemic and how that public health crisis revealed much of what Lewis warns against. On this episode, Dr. West explains how scientism harms scientific progress. He also reveals how Lewis refutes the idea of scientific materialism, how scientism leads to moral relativism, and how we can bring science back into alignment with older, deeper human truths. Let's jump right back in.

[00:02:19] Speaker C: How does scientism and scientocracy harm genuine scientific progress?

[00:02:24] Speaker D: Yeah, well, I think it's what I've.

[00:02:26] Speaker E: Already alluded to, which is, if you have the idea that the country should.

[00:02:32] Speaker D: Be or your nation society should be.

[00:02:33] Speaker E: Guided and dictated by science, and that there's a group of people that are dubbed sort of the spokespeople for science.

[00:02:41] Speaker D: That breeds well, for one thing, it.

[00:02:45] Speaker E: Ties science to the quest for power.

[00:02:47] Speaker D: And so actually, this is something Lewis did point out in this and other.

[00:02:51] Speaker E: Essays, which is if you fuse not.

[00:02:54] Speaker D: Only expertise and knowledge, if you fuse.

[00:02:59] Speaker E: That with the power to basically dictate to everyone else, that's an unholy combination.

[00:03:06] Speaker D: And it's not just about science. I would say I'm a Christian, so.

[00:03:09] Speaker E: I think we're fallen, I think we're sinful.

[00:03:11] Speaker D: So I think it's not just about.

[00:03:13] Speaker E: The abuse of science, it's about the abuse of any sort of expert knowledge.

[00:03:16] Speaker D: And I would agree with Lewis, which.

[00:03:19] Speaker E: Is so in past ages you had, say, in the Christian Middle Ages, we actually have some people today, I think wrongly, who are so called quote Christian nationalists, unquote, who are upholding this idea that you want religious power fused with the state.

[00:03:35] Speaker D: I think that's a terrible idea.

[00:03:37] Speaker E: That theocracy is just as bad as Scientocracy. And Lewis's point was this when you fuse some claim for superior, absolute knowledge with power, that's an unholy combination, and you're actually encouraging corruption. Because if you're someone let's be honest, anthony Fauci was not a brilliant scientist.

[00:03:59] Speaker D: If you know anything about his history.

[00:04:02] Speaker E: As a public science official, not trying.

[00:04:04] Speaker D: To demonize him, but he wasn't a great scientist. Francis Collins, now I'm going to get into trouble.

[00:04:09] Speaker E: Actually, he isn't really a brilliant scientist either. Both of those people made a career in government power positions. If you fuse just like in the.

[00:04:20] Speaker D: Old days, where governments wanted to speak in the name of God and the.

[00:04:25] Speaker E: Church wanted to exert earthly power, well, if you want to be a tyrant, how do you do it? You fuse yourself with thus Seth, the Lord, and you had the divine right of kings. You had various religious church officials try.

[00:04:39] Speaker D: To exercise a civil power, and it was a mess.

[00:04:41] Speaker E: It was horrific.

[00:04:43] Speaker D: Similarly, and again, Lewis said lewis said.

[00:04:47] Speaker E: You know, he detested Theocracy. That's also why he detested Scientocracy, because if you fuse science, which is the search at some point is the search for knowledge about the natural world, which is a very good thing. And Lewis was not anti science, and neither I. But if you fuse the scientific knowledge with the right to power, you're really changing the incentive structure, and you're really asking to bring in little petty and not so petty tyrants into science, quote, unquote, because they really want to rule your life. It's not because they're such good scientists. In fact, that's what we see.

[00:05:22] Speaker D: I mean, during COVID again, there were.

[00:05:24] Speaker E: Many really well standing scientists.

[00:05:26] Speaker D: Jay Praticero at Stanford, those some at.

[00:05:29] Speaker E: Harvard and Yale who had a different view, but they were muzzled by, I'd say, small minded people like Anthony Fauci and even Francis Collins.

[00:05:37] Speaker D: Now that we have gotten a lot.

[00:05:39] Speaker E: Of the Freedom of Information Act requests, francis Collins was talking about people who didn't agree with him on some of the COVID policies as being fringe epidemiologists.

[00:05:49] Speaker D: Well, Francis Collins wasn't even an epidemiologist, and he certainly wasn't outstanding, period.

[00:05:55] Speaker E: And so he was basically calling people.

[00:05:56] Speaker D: At Stanford and Harvard and Yale because.

[00:05:59] Speaker E: They disagreed with him as fringe.

[00:06:01] Speaker D: I mean, that tells you something about.

[00:06:03] Speaker E: The dangers of fusing any sort of expert knowledge with political coercive power.

[00:06:11] Speaker D: So, yeah, I think this harms genuine.

[00:06:13] Speaker E: Scientific progress because it puts the people speaking for science in a way of that they can easily shut down any.

[00:06:22] Speaker D: Sort of debate or disagreement.

[00:06:23] Speaker E: Science proceeds based on debate and argument.

[00:06:28] Speaker D: And the reason why we have certain views today that are different from two.

[00:06:32] Speaker E: Or 300 years ago is that there was allowed to be vibrant arguments anytime science is fused with the power to suppress debate that actually harms genuine scientific progress, right?

[00:06:45] Speaker C: Especially when you have big tech playing the willing part of the know, helping governments and leaders in their opposition to free science, as it were. Well, another idea that Lewis challenges in his work is the idea of scientific materialism, the belief that matter is the sole and fundamental reality. What's wrong with this idea, and how.

[00:07:06] Speaker B: Does Lewis refute it?

[00:07:08] Speaker E: Yeah, so materialism goes back a long.

[00:07:10] Speaker D: Ways, at least to the ancient Greeks.

[00:07:12] Speaker E: That were just blind matter in motion.

[00:07:14] Speaker D: And because it was just so outlandish.

[00:07:17] Speaker E: To most people, it was never the majority view.

[00:07:20] Speaker D: But then we get to sort of the 18th, 19th centuries, and we have.

[00:07:24] Speaker E: People taking some new discoveries in the physical sciences and chemistry in physics, too.

[00:07:32] Speaker D: And trying to claim, oh, well, we now have this overwhelming empirical knowledge that.

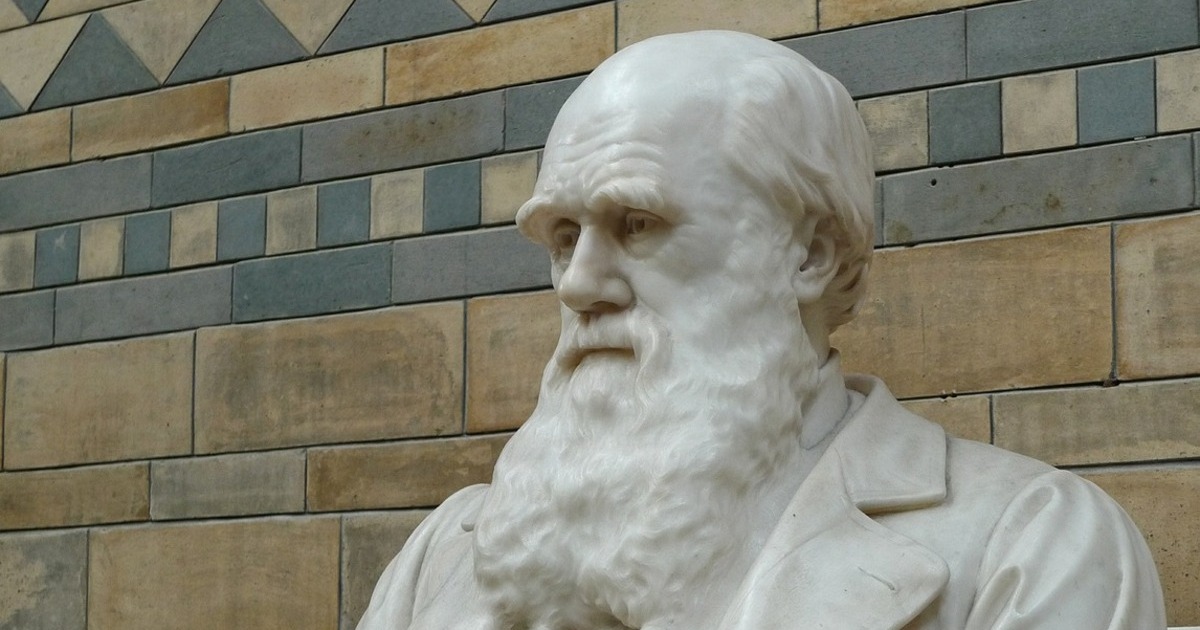

[00:07:37] Speaker E: Shows that we are just blind matter in motion. And then you have Darwin, who sort.

[00:07:40] Speaker D: Of takes some of these ideas into.

[00:07:42] Speaker E: Biology and saying, yeah, blind matter and motion ultimately can explain even life itself, including human beings.

[00:07:48] Speaker D: So that's sort of the belief.

[00:07:51] Speaker E: There are many things wrong with it.

[00:07:53] Speaker D: I think, for sake of time and other things.

[00:07:55] Speaker E: Lewis's biggest critique of that view is that if you hold that view, it's pretty much hard to have any belief justified belief about mean. So science itself is a rational process that assumes the laws of logic.

[00:08:14] Speaker D: It assumes a lot of things. It assumes that rationality is real and.

[00:08:18] Speaker E: That we can have access to the real world. But if our minds are ultimately the product of this blind and purposeless material process, there's no real reason to have confidence in our own minds. And this was his sort of critique of sort of Darwinian accounts, among others.

[00:08:38] Speaker D: Of how we got the mind.

[00:08:39] Speaker E: If the mind developed through this blind, mechanical process, basically only because it helped physical survival, on what basis should we.

[00:08:49] Speaker D: Have confidence that our minds are telling.

[00:08:51] Speaker E: Us anything true, either about Darwinian theory or anything else?

[00:08:56] Speaker D: And today, this idea, which Lewis sort of got from a book, at least.

[00:09:03] Speaker E: In part, called a series of lectures by Arthur Balfour, who's best known for.

[00:09:07] Speaker D: The Balfour Declaration, the British Prime Minister.

[00:09:10] Speaker E: But Arthur Balfour was sort of a gentleman philosopher, and he gave the Gifford Lectures that became a book called Theism and Humanism, which Lewis listed as one of the top ten books that influenced him the most. And in that book, Balfour basically makes.

[00:09:24] Speaker D: The idea that if you're trying to.

[00:09:25] Speaker E: Explain mind or morality for that matter, or these other things as just being produced by things that are less than rational, less than mind, or less than moral, it's like you're getting something from nothing. I mean, how do you get mind from a mindless process? He thought that was contradictory. And Lewis, in his book Miracles and in other essays made that same argument.

[00:09:47] Speaker D: Today we have people like the great.

[00:09:50] Speaker E: Philosopher at Notre Dame, Alvin Plantiga, who's made the same argument even more rigorously. But that argument goes back to Lewis, goes back to Balfour, and in some.

[00:10:00] Speaker D: Sense actually goes back to Plato.

[00:10:01] Speaker E: But Lewis really made that argument.

[00:10:04] Speaker D: So I think Lewis argued that materialism.

[00:10:07] Speaker E: Really was self contradictory because our belief in materialism is based on logic and reason, supposedly. I mean, we're offering arguments for materialism, but why should we think that our beliefs in materialism, our arguments for materialism, are true if our very minds, if they were produced according to the way materialists think, weren't produced necessarily to produce truth?

[00:10:30] Speaker D: I mean, we've shaken our confidence in the mind so much that we have.

[00:10:34] Speaker E: No reason to even believe in materialism. And Lewis noted, by the way, that Steve Meyer wrote a great book called.

[00:10:40] Speaker D: Darwin's Doubt, which dealt with another of Darwin's doubts. But I would argue that really Darwin's.

[00:10:45] Speaker E: Biggest doubt was on this very issue. Darwin wrote in some letters to people know one of the things that troubled him, I guess it didn't trouble him.

[00:10:54] Speaker D: Enough, but that did trouble him was.

[00:10:56] Speaker E: That this gnawing doubt that if his mind if he was the product of the type of unguided material process that he was claiming, why should he even have confidence in what his mind was saying? And it's interesting Lewis read Darwin's autobiography. You can go to the Wade center at Wheaton college, and you can hold it in your hands.

[00:11:16] Speaker D: And if you look at the version.

[00:11:18] Speaker E: Of the autobiography that Lewis had, the edition, this area where Darwin is raising this question, but how can he trust his own mind, given his belief and.

[00:11:31] Speaker D: How the mind came about?

[00:11:32] Speaker E: Lewis underlined it. So Lewis understood that this was the Achilles heel of materialism. Is it really refutes your mind. It refutes the very scientific claims that if you say that science proves materialism but you have no grounds to believe in science to begin with, you're in a world of hurt.

[00:11:51] Speaker C: And this does play into morality, too. I mean, scientism can work its way into moral relativism because in the end, there's no way to validate moral knowledge. So morality becomes subjective.

[00:12:02] Speaker D: Yeah.

[00:12:03] Speaker E: So if physical science, modern materialistic science.

[00:12:06] Speaker D: Is the only aspect way you get.

[00:12:08] Speaker E: To truth, well, then that means that.

[00:12:09] Speaker D: Things like morality mean you have to.

[00:12:14] Speaker E: Deconstruct them as not that they're sort of this transcendent moral truth across time or situation, but that all it can be is some sort of accidental product of this materialistic process. And of course, Lewis did write about that.

[00:12:28] Speaker D: And of course, in our own time.

[00:12:30] Speaker E: Probably the biggest claim for this in.

[00:12:33] Speaker D: The name of science is sort of.

[00:12:34] Speaker E: Darwinian accounts of morality, that morality developed basically in service of natural selection to promote physical survival.

[00:12:40] Speaker D: And that means that in whatever your.

[00:12:42] Speaker E: Society, that the needs for survival are.

[00:12:45] Speaker D: That'S going to dictate morality.

[00:12:46] Speaker E: And so morality simply is an accidental product of this process for what you need in your own society for physical survival and reproduction.

[00:12:55] Speaker D: And that means that over time, in.

[00:12:58] Speaker E: A cross situation, morality can be radically relative based on your survival needs. I mean, Darwin wrote about this in his book The Descent of man, and he tried to put a lipstick on the pig. He tried to make it sound, oh, well, this shows a natural basis in biology for morality.

[00:13:16] Speaker D: But many of his followers, even we mentioned earlier, Aldous Huxley, well, his grandfather.

[00:13:21] Speaker E: Thomas Henry Huxley, when it came to claiming that this amoral materialistic process could explain morality, that was too much for him to the nature somehow proved traditional morality, which was sort of darwin tried to make the claim that was too much for Thomas Henry Huxley.

[00:13:39] Speaker D: He actually said, no, what we do.

[00:13:41] Speaker E: What we see in nature is sort of tooth against claw and trying to.

[00:13:46] Speaker D: All the things we see in nature.

[00:13:47] Speaker E: Euthanasia nature, other things.

[00:13:51] Speaker D: We'Re trying to fight against that.

[00:13:52] Speaker E: So morality is the fight against that. So morality has to come from someplace else.

[00:13:56] Speaker D: Now, Thomas Henry Huxley didn't have a.

[00:13:58] Speaker E: Clue about where it came from because he didn't want to go there to the traditional explanations. But in any case, yeah, Lewis did also critique Darwinian accounts and materialist accounts of morality because it's very hard to have some sort of permanent, transcendent morality if this is your view of science, if you have a scientific or a scientific materialist view of nature and human society.

[00:14:23] Speaker B: Yeah, absolutely. Well, in The Abolition of man, lewis.

[00:14:26] Speaker C: Writes that modern science requires restraint, and that restraint is unlikely to come from inside science itself. It must be arrested, it must be recalled to a position of submission to a deeper and older set of human truths. What would you say those deeper and older human truths are? And how do we go about restraining science today?

[00:14:47] Speaker E: Yeah, Lewis actually he doesn't fully tease.

[00:14:50] Speaker D: This out, but in the end of.

[00:14:51] Speaker E: The Abolition Man, he actually calls for a new kind of science, a regenerate science.

[00:14:56] Speaker D: And so I would argue that it's.

[00:14:58] Speaker E: True that modern science doesn't have the resources to restrain itself. I think that's the problem of its conception. You have to have a conception of science that does have those restraining resources.

[00:15:13] Speaker D: Science has to be reconceptualized so that.

[00:15:16] Speaker E: Morality or views of human dignity, views of the idea that humans aren't God, need to be built into the philosophy of science. So the philosophy of science, every discipline has an underlying philosophy. Well, that's true of science, it's true of chemistry, it's true of biology.

[00:15:34] Speaker D: And so this is one reason why.

[00:15:36] Speaker E: There are some people who they themselves aren't they say they don't buy into scientism, but they want a view of.

[00:15:43] Speaker D: Science where they think that, well, we want to have our philosophy and metaphysics.

[00:15:48] Speaker E: And things over on one side and then just our science, our nuts and.

[00:15:54] Speaker D: Bolt science on the other side.

[00:15:56] Speaker E: Well, I'd say we've lived through that in the last century of trying to do that, and it doesn't work. If your conception of science doesn't have in and of itself limiting factors, it will eat everything else up. You can't just have well, I have my philosophy.

Of course, scientific claims in the name of philosophy or getting into value questions is wrong. But we know that from philosophy, not from science. Well, if you say that people speaking within science, from that kind of science, aren't going to accept it.

[00:16:29] Speaker D: I mean, you may say that science.

[00:16:31] Speaker E: Doesn'T refute philosophy or morality. But if the scientists view and the people who speak for scientists, if that's.

[00:16:38] Speaker D: Their view of science, that science only shows the reality of things that are.

[00:16:44] Speaker E: Sort of material quantifiable on and on.

[00:16:48] Speaker D: Then science is going to continue to, in the name of science, to gobble everything else up.

[00:16:54] Speaker E: So the solution, I think actually I.

[00:16:57] Speaker D: Think my colleagues in the intelligent design.

[00:16:59] Speaker E: Movement are hitting on this, which is that at the basis of science, science itself needs to recognize that it points to this larger transcendent basis both of right and wrong, but also of design versus no design.

[00:17:14] Speaker D: And that that is an irreducible component of science itself.

[00:17:19] Speaker E: And if you understand that the world and the universe is designed well, then one of the questions you have is obviously the designer is, I would say, a whole lot more intelligent and a whole lot probably wiser than we are. And so some of your ideas to.

[00:17:37] Speaker D: Remake nature that Lewis writes about in that hideous strength and things that turn.

[00:17:41] Speaker E: Out horrific, things like eugenics or other things you should be properly skeptical of that. Not just on the notion that these.

[00:17:50] Speaker D: Scientists may not know what they're saying, it may be bogus science, but on.

[00:17:53] Speaker E: A broader level, who are we to think that we can reinvent nature?

[00:17:57] Speaker D: In other words, it closed nature with.

[00:17:59] Speaker E: A moral grandeur that you need to respect.

[00:18:03] Speaker D: And with some of this things about.

[00:18:05] Speaker E: Creating transhumanism, creating a new human being and stuff. Some of the people who are criticizing that, even on the secular conservative side, who want to embrace sort of a Darwinian view of nature, that's sort of anti intelligent design, but then also want.

[00:18:19] Speaker D: To claim, well, we don't believe in.

[00:18:22] Speaker E: Human cloning or transhumanism. But I want to say why really.

[00:18:27] Speaker D: Their only objection when it comes down.

[00:18:28] Speaker E: To it is, well, we don't know.

[00:18:30] Speaker D: Enough yet, or it might turn out bad. Well, but where do you get the.

[00:18:33] Speaker E: Standard of good and bad from? And if you really think nature is the product of this accidental, blind, evolving process with no higher end in view, if we can do better, why not? Now, if you have a design view of nature that there's this transcendent standard that sort of nature ultimately is responsible for. I think it gives you more humility and less hubris about mucking up nature.

[00:19:00] Speaker D: It doesn't mean you shouldn't try to.

[00:19:01] Speaker E: Improve, it doesn't mean you shouldn't try to ameliorate things, but it does place.

[00:19:05] Speaker D: Like I said, I think the best way to explain it is we have.

[00:19:08] Speaker E: No right to play God, but that presumes you believe there's a God or.

[00:19:12] Speaker D: An intelligent designer that you don't want to play. And that, I think, needs to be.

[00:19:17] Speaker E: Built into the very conception of science. Science can't be this rogue outlier for the rest of human knowledge or human ethics, right?

[00:19:27] Speaker C: And it doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's part of a more all encompassing view of reality and of humanity, and we need to make it that way. Well, if Lewis were with us today, final question for you. Observing the events of the last few years, and of course, looking ahead at where we might be headed, given all the hints, what advice do you think he would give us?

[00:19:47] Speaker E: Pray?

[00:19:48] Speaker D: I don't know. It's pretty bleak. And I think he would have found that there. Although anyone who is a person of faith, let alone I would argue if.

[00:19:59] Speaker E: One happens to be a Christian, which.

[00:20:00] Speaker D: I happen to be, that there are.

[00:20:02] Speaker E: Great grounds for hope that go well beyond where we're living right now. I would say that if you want Lewis's advice, I would encourage everyone to read that Hideous Strength, which I think is one of the great novels against scientocracy in the English language, because it's all there. Whether it be the manipulation of the.

[00:20:22] Speaker D: Media, whether it be the manipulation of.

[00:20:24] Speaker E: Sexuality, whether it be these transhumanist ideals.

[00:20:28] Speaker D: That we're going to evolve ourselves into.

[00:20:31] Speaker E: Better creatures, the denial of morality in.

[00:20:35] Speaker D: The name of science and the corruption.

[00:20:37] Speaker E: Of science when it's fused with government.

[00:20:39] Speaker D: Power and the corruption of academia that.

[00:20:43] Speaker E: Goes ultimately into nonsense that ultimately undercuts any sense of objective truth or meaning. Which, for those of you who have read that hidden strength without giving it away by the end, that's pretty clear.

All I'll just say is the Tower of Babel.

[00:21:01] Speaker D: Just think what happened after that. And you'll know what I'm talking about if you've read that. So I think people should read that. And I think the main thing is actually getting a little more serious here.

[00:21:14] Speaker E: If you understand the problem, that is the first step toward a solution. And so the reason why the things happened that Lewis lived through in the 1930s and early sixty s, the reason why some of those horrific things happened was because people had a very naive view of science.

[00:21:34] Speaker D: In many ways, at the beginning of.

[00:21:35] Speaker E: The 21st century were like at the beginning of the 20th century, you had a lot of naive views, sort of pre world war I, that science could be our savior. And even despite the horrors of world war II, going into post world war.

[00:21:48] Speaker D: II, you had people think, is the age of the jetsons of that cartoon. Or here in Seattle, we had the.

[00:21:55] Speaker E: 21St century world's Fair that gave us the Space Needle, which is a fun monument.

[00:22:03] Speaker D: But this idea that through science it.

[00:22:06] Speaker E: Couldn'T just help us for better physical things, which of course science can do many benefits, but somehow it was going to lead us to this utopia.

[00:22:14] Speaker D: I think that if you recognize that's.

[00:22:17] Speaker E: Not true and you recognize the dangers of claims made in the name of science, then you actually do have some.

You might be able to avoid some of the worst excesses, I think like the COVID pandemic. I hope that you mentioned sort of the emergency powers.

[00:22:33] Speaker D: One of the things coming out of the COVID pandemic that people should be.

[00:22:35] Speaker E: Concerned about, regardless of where you are in the political spectrum, regardless of where you are on whether you're formasking not formasking for vaccine mandates or not for vaccine mandates.

[00:22:47] Speaker D: One thing that I think you should.

[00:22:48] Speaker E: Come out is that many of the.

[00:22:50] Speaker D: Lockdowns and policies that were done on.

[00:22:53] Speaker E: People were done largely at the behest of unelected government officials or, in some cases, the executive branch that was elected.

[00:23:01] Speaker D: But there was simply rubber stamping.

[00:23:03] Speaker E: Legislative assemblies had nothing to say.

[00:23:08] Speaker D: And in some cases the emergency powers lasted for years.

[00:23:11] Speaker E: I think there were some places that even this year, early this year, finally let go of their emergency declarations. Well, in some states they have actually tightened that up.

[00:23:21] Speaker D: And I think that that is something that as a society we need to look at.

[00:23:24] Speaker E: We really need to tighten up who can issue and the limits on emergency powers. And I would say require after the first 30 or 60 or 90 days.

[00:23:35] Speaker D: Them to actually be approved by a legislative assembly where you can force an.

[00:23:38] Speaker E: Actual debate with your elected representatives.

[00:23:41] Speaker D: So I do think there are some.

[00:23:43] Speaker E: Things that once you're forewarned, you're forearmed.

[00:23:46] Speaker D: And that you can be raising questions.

[00:23:48] Speaker E: But people first need to know the questions to ask. And I think Lewis is a good place to start.

[00:23:52] Speaker C: Some great advice there. Well, Dr. West, thanks for taking the time to commemorate Lewis's legacy with us today. I hope you'll be back soon to continue the discussion.

[00:24:01] Speaker D: I hope so too.

[00:24:02] Speaker C: Thanks for a book length treatment on these topics. Be sure to get a copy of the Dr. West edited volume the Magician's Twin C. S. Lewis on science, scientism and society. And if you want to watch it in video form, like I said, he has some great documentaries up on YouTube and elsewhere as well. Well, that's all the time we have. For Idthuture. I'm Andrew McDermott. Thanks for listening.

[00:24:26] Speaker A: Visit

[email protected] and intelligentdesign.org. This program is copyright Discovery Institute and recorded its center for Science and Culture.