Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: In a way, people I felt had somehow closed their account with the traditional God. And when Darwin came along and said, oh well, there's a way of explaining creation which doesn't, which bypasses God altogether, they said, yes, yes, that's what we're looking for.

ID the Future, a podcast about evolution and intelligent design.

[00:00:24] Speaker B: Did Charles Darwin's theory theory triumph on purely scientific grounds, or are there other reasons beyond empirical science that gave it broad acceptance and enduring popularity?

Hey, everyone. Welcome to ID the Future. I'm Andrew McDermott, your host. Well, today I begin a conversation with professor emeritus and author Neil Thomas about his new book, False Darwinism as the God that Failed. Over two episodes of the podcast, we'll look at some of the problems with the theory itself, as well as how it managed to triumph for so long and how modern science is undermining the Enlightenment worldview upon which Darwinism relies.

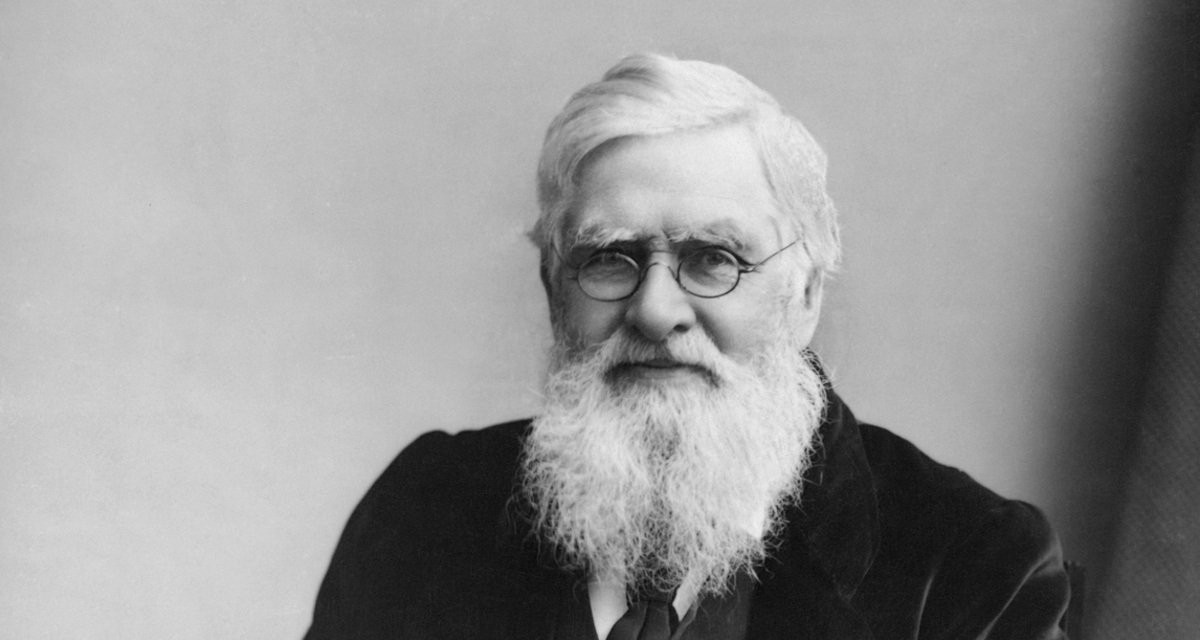

Thomas is a reader emeritus in the University of Durham, England, and a longtime member of the British Rationalist Association. He studied classical studies and European languages at the Universities of Oxford, Munich and Cardiff before taking up his post in the German section of the School of European Languages and and Literatures at Durham University, 1976.

He has published over 40 articles in a number of refereed journals and is author of a number of books, including the 2021 Discovery Institute Press title, Taking Leave of Darwin, A Longtime Agnostic Discovers the Case for Design.

Well, welcome to the podcast, Neil.

[00:01:43] Speaker A: Hello.

[00:01:45] Speaker B: You know, I don't know what it is, but I love making connections between things we know and experience today and how those things began. Call me an historian, I suppose. The roots, the connections to other things, just getting that full story. And so it's really rewarding when we can do that and know the roots of something because I think it gives us a richer understanding and appreciation in our present moment. I was excited to learn about your new book, actually probing the roots of Darwinism and exposing the theory as a God that failed.

So let's begin here by reminding our audience about your own journey. It always starts there. And you describe yourself as a longtime Darwinist and agnostic who was surprised to find modern evolutionary theory rests on a very rickety foundation. You tell this story in your 2021 book Taking Leave of Darwin. You went from being a member in good standing of the Darwinian establishment to one ready to bid the theory farewell. I like how you put it in the book. You said that when referencing Darwin as well as his latter day adherents, you felt a disquiet at discovering that all their scientific Sounding livery were but the regalia of so many empty references carried along by magical thinking. It's a great way to put it. Can you tell us about that in your own words?

[00:03:05] Speaker A: Yes, I mean, I should. Empty reference is a technical linguistic term. Term. It means something that seems to have a meaning but doesn't.

For instance, like the man in the moon or if you can think of the Victorian seances, ectoplasm, which is supposed to be an emanation of a dead person materializing in the presence of.

[00:03:32] Speaker B: So.

[00:03:34] Speaker A: And I think that unfortunately, biology has succumbed to these empty reference in the sense that even natural selection, the cardinal principle of what we're talking about, is not, in fact what it seems to imply. There is no actual selection.

Essentially, it means preservation of those things which do well and which can go on. It has no creative ability at all, and it does not create new creatures.

This was pointed out long ago to Darwin by Sir Charles Lyell, the eminent geologist.

And while Darwin did sort of grudgingly say, yes, well, I suppose you're right, he never really took to it or never really modified his theory.

So in a way, what we're dealing with is something which doesn't actually make sense logically.

That is my grouse with it.

So preservation is conservative, cannot create, and certainly cannot select.

[00:05:14] Speaker B: Yeah, and I like the word you used. You felt a disquiet as you were around scientists who had all the scientific sounding livery, as you say, the regalia of Darwinism. But you just. There was a, there was a gap there between the, the, the, you know, idea of the theory and the theory itself and how much it made sense. I suppose there's two groups of people, isn't there? There's the, the people that will, will. Will just buy into Darwinism, no matter how they feel personally about it for various reasons or those that just cannot stomach it and eventually have to stand up and say there's something wrong.

And you, of course, did that with taking leave of Darwin. What inspired you to tell your story?

Was it just something you had to get off your chest, as it were?

[00:06:06] Speaker A: I think so.

I think I would regard myself as something of a whistleblower that I felt that I was crying fire in a cinema that really was on fire.

I wasn't being malicious. I was actually trying to warn people that they'd been cons for more than 160 years.

And I suppose at my age, I felt that what I write now is going to be a sort of legacy text. I'm using the word legacy text as something that future generations can read and take further, take the baton on further because I'm obviously not going to last forever.

[00:06:57] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. Well you've done us a service in sharing your disquiet and the reasons for it.

Well, you have a background and expertise in European intellectual history as well as in languages and linguistics.

It turns out that's great experience and knowledge to be able to really evaluate Darwinism, Charles Darwin, but also the milieu around Darwin and the whole time period and what people were thinking, that's a great skill set to be able to tell this story. How did those things that you've learned and studied and taught, how did those things help you write this book?

[00:07:40] Speaker A: Well, I think that having been a modern languages major and later professor, this made me sort of allergic to nonsense and reference, I mean notes, subjects.

[00:07:57] Speaker B: I like that. Allergic to nonsense.

[00:07:59] Speaker A: And also I think that looking at European history I, I was able to trace in somewhat minute detail, especially when I did a bit more recent research how religious views changed and how theism became Deism and then how people felt that Deism was not a very red blooded kind of religion and they thought, well, what's the point of having a non interventionist God?

We would prefer to have somebody who intervene.

So in a way people I felt had somehow closed their account with the traditional God. And when Darwin came along and said, oh well, there's a way of explaining creation which bypasses God altogether. They said yes, yes, that's what we're looking for.

So it was an historic, it was a buildup of historical forces which you can only know about if you've done, if you've, if you've studied the history of Europe in the last few centuries.

[00:09:08] Speaker B: Yeah, and you lay that out pretty spectacularly. You know, you build, build that story. So that by the time we're again looking at Darwin and his theory, we sense that, we understand that this wave of scientific materialism and anti theism as you put it, that was sweeping, you know, certain people. Now of course it wasn't. There was a, there was still a huge body of believers who, who leaned in, in their faith even when signs was not, you know, was not sharing or, or, or joining in with that belief. But, but yeah, I like the way that you, you, you paint that picture. Now Darwin was by no means the first man to be thinking about evolution. In the first half of the 19th century. There was a group of scientists in Europe who were intrigued by the idea of animal types transmuting was the word back then into other species. And they were on the hunt for a vera causa or mechanism that might validate their musings. That's right. But it's also the case, you point out that the common opinion of the leading man of science in the first half of the 19th century, so leading into Darwin's publication year, they tended toward a form of deism and wouldn't easily tolerate a theory based on chance or, or even miracles for that matter.

So what was the reaction then when Darwin dropped in his abstract detailing this proposed mechanism of natural selection?

[00:10:37] Speaker A: Well, I think that people were hoping, almost praying, for such a mechanism to come forward. Because remember that Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, in company with that group of people in France that we know as Les Philosophes historically, had indeed entertained the possibility of the transmutation of species. Transmutation, that actually was an old word culled from alchemy.

And Erasmus Darwin took it over to refer to the development of animals from one type to another.

But it remained a hobby horse of particular coterie of eccentric scientists, in many people's view, until they could put their hands on some true cause of change.

And that is what Darwin came up with.

I've said that I do not believe that the word natural selection is intellectually coherent, but other people were willing to believe that it was. And that is how the whole bandwagon got launched and why people felt, oh, well, Charles Darwin has come up with a scientific explanation. We'll go with that, since we have little faith in the God of our fathers to have created the whole universe.

[00:12:32] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. And there were some early strong critiques of his work, but somehow the mystique and the mythology of Darwinism was able to get past that and, you know, be successful. Nevertheless, how did Darwin respond to these early critiques and how did he try to downplay the element of chance in his theory to appease his Victorian colleagues?

[00:12:59] Speaker A: I think he reacted with a complete lack of contrition.

He did not want to listen to anybody else.

And he also went in for a little bit of obfuscation by framing his arguments in such a way as to take the emphasis off chance and imply that there was some lawfulness or some regularity unspecified, which accounted for these processes of change.

And people have studied this before. I mean, the point is, the only instance I have ever known of one species changing into another is a short novella by Franz Kafka called Metamorphosis Bifew antlo in German, where the hero Gregor Samsa is changed miraculously into a beetle like creature. But this, of course is fiction. Not fact.

And I do not take that as a parallel to anything in Darwinianism. But I do think that, that what Darwin was suggesting was in a sense Kafkaesque in the negative sense that we use that word.

[00:14:36] Speaker B: Yeah, that's a good connection.

Did that story come out after Darwin's theory?

[00:14:42] Speaker A: No, it came out.

[00:14:43] Speaker B: Was it before?

[00:14:44] Speaker A: Well, wait a minute. No. Then yes, it's something you should ask that because before I was thinking was this Darwin, was this Kafka's satire and Darwin? Yes, that's a good point. I hadn't thought of that. But it could be. It's a sort of reverse Darwinism, isn't it? Where a more developed species then descends into a beetle like creature.

[00:15:11] Speaker B: Yeah, well, natural selection, let's talk about that term for a few moments. What did Darwin mean by it and does he change the meaning of the term as it was commonly used?

[00:15:22] Speaker A: Oh, very much so, yes.

Natural selection was a term used by British breeders and pigeon fanciers and so on for what they could not do by selective breeding.

There were certain, what used to be called sports.

There were certain exceptions. They couldn't necessarily engineer genetically by mating of certain animals.

Nature sometimes just came in and spoiled their efforts at providing what they wanted.

In other words, natural selection originally meant something like nature's serendipity, that over which we have no power to control.

Darwin strangely used this term and stood it on its head and said, no, natural selection is the way that nature selects and creates all the creatures in the world.

It was. I mean, some people have said that this is an apotheosis or deification of nature, as if Nature herself was some kind of goddess who could choose and willow out the bad bits and encourage the good bits and then proceed to make ever more complex creatures.

And this was something that maybe was in the air more in the 19th century than now, but now it seems somewhat absurd.

And as I say, I don't believe in some natura or natural goddess who is doing this widowing process. But I think I've got a feeling that Darwin in his heart of hearts did have that idea in mind. Which is why he stood out against those people who said to him, well, you know, nature cannot select. He really stood out against that. And I can only think that he had this ide fixe in his mind of nature being a kind of substitute deity.

Right.

[00:18:01] Speaker B: And that was my next question. Does he cheat here by ascribing to natural selection the very powers that he's taking away from an intelligent designer, a God?

What do you think?

[00:18:16] Speaker A: I think that he was not cheating.

I think that he was self deluding in a way because remember that his attitude to the Christian faith was very much riven. I mean, he described himself in a letter in 1879 as being a theist.

And yet he wanted to create a theory which would do away with God, that those two things aren't actually compatible logically way.

So I think he often said when asked about the existential imponderables of life that we all have to face. Well, I'm not sure I'm confused.

And he was, in a way, he was remarkably modest because when he was younger he said that when he was in school that he, quote, I am not as clever as my younger sister.

I mean, that's very admirable to be so modest. But talking about it seriously, it means he's not the intellectual guru that later generations have made him out to be.

He was a bit of a mixed up kid, to use a slang expression, right up until older age.

[00:19:47] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. Trying to wrestle with the tensions that came with life. And it's interesting, you know how he does that. Well, the topic of Darwin's belief in God is one we could spend a lot of time discussing.

[00:20:02] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:20:02] Speaker B: But I just want to touch on it a little more briefly here. You described Darwin as a man of two minds fencing with God and never losing the sense of God as a real presence.

You know that one of the books that Darwin brought with him on his famous voyage on the Beagle was Milton's Paradise Lost.

How does this famous poetic work serve to illustrate the tensions in Darwin's fraught and conflicted attitude to religion?

[00:20:30] Speaker A: Yeah, this is an idea that occurred to me.

It hasn't been mentioned by any of his biographers.

They've said that he took various books onto the Beagle with him. I mean, he took the first edition of Geology book by Sir Charles Lyell because that came back in 1830 in time for the first.

But nobody has mentioned the fact specifically that he took Paradise Lost with him. Now the point about this is, the reason I highlight this is because Paradise Lost is certainly the first few books concentrate on the expulsion of Satan and the other rebellious angels from heaven by a somewhat vindictive God, or so it seems.

So part of Darwin felt that God could be a sort of Old Testament, rather sanguinary kind of chieftain.

And he also was not comfortable with the fact that the doctrine of hell, which was more current in the 1830s than it is in our own age, would consign some of his Fellow doubters to perdition, just like Satan and the fallen angels were consigned to Tartarus, which is more or less a synonym for hell in Milton's cosmology.

So I think that. I mean, Paradise Loss is a marvelous work in its own right. I mean, you can't. Milton was a wordsmith who was second to none. But it also has this sort of nagging theme, is God is just as we would like him to be.

In the 1930s, a critic called William Empson wrote a book about Milton's God in which he said.

Empson was, by the way, an atheist who said, well, if you're being serious about things, the God that emerges from Paradise Lost is more like a devil than a God. So this split in Darwin can be seen in other people as well, and I hold in on that as being particularly interesting piece of reading for him to take because it's a bit left of center, isn't it? Why would you take it unless you had some real interest in the substance of it?

[00:23:37] Speaker B: Yeah, I mean, he could have taken his Bible, he could have taken works of antiquity from the church fathers, but it was Paradise Lost. And I agree with you that I think it does kind of illustrate the. The conflict, the inner conflict that he had.

I also recall you mentioned that in. In one of the editions of the Origin, he wrote a private note, you know, asking himself, does this make me an atheist? And then he underlined his own answer, no. You know, in.

[00:24:09] Speaker A: In one of his private diaries, which I. I got that from the book that called Darwin's Dice, which came out in 2015, about somebody who'd actually studied the private thoughts of Darwin. So I think, yeah, psychologically, the private lies are the subconscious.

I think you're onto something there. I think that was probably right. Yes.

[00:24:38] Speaker B: Well, you point out that Darwin used metaphors quite liberally, like his Tree of Life, the idea of natural selection itself, and various ways to portray nature, such as a destroyer as well as a nurturer.

[00:24:51] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:24:52] Speaker B: How does his use of metaphors, his speaking metaphorically, impact his theory, do you think?

[00:24:59] Speaker A: Well, I think that I've already talked about the fact that he felt that nature was some kind of quasi goddess, but he didn't necessarily. He wasn't so polyamorous as to think that there was no suffering in the world.

So I think he was aware of both sides of the argument.

Um, and he.

Again, he wasn't quite sure, but these thoughts were sort of bubbling up inside him and perhaps they were never truly resolved even until the day of his death.

[00:25:51] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. But he did use metaphor quite a bit.

And do you. Do you think that works for him or was there problems with using metaphors? I mean, in some ways you have to turn to metaphor. But do you think he did it successfully?

[00:26:07] Speaker A: I think that he did it successfully in this sense, that it revealed more of him than he might have realized.

A book came out about 40 years ago by somebody called Dov Ospavat, who was settled in America, and he more or less said, and I'm simplifying now somewhat, that Darwin was essentially a closet theologian, that he believed that because natural selection was always something which led upwards and better things rather than going downwards into degradation and deprivation, that that was a kind of faith, a kind of faith in a good deity who would help humanity in its upward ascent.

So, yes, I think that his metaphors are not just metaphors. They are revealing metaphors. They are revealing of his subconscious.

[00:27:34] Speaker B: That's a great point. Yeah, yeah, very interesting.

Well, in a chapter titled Piecing Together A Theory, you say that Darwin's ideas resembled more of a cumulative, essentially social construction of reality than the result of straightforward, empirically demonstrable findings.

[00:27:51] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:27:52] Speaker B: How was Darwin's theory informed by other scientists and thinkers, from the ancient Greek and Roman natural philosophers to the likes of his own mentor, Charles Lyell.

[00:28:02] Speaker A: How many hours have we got?

[00:28:05] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah.

Seriously, these. These are big questions and you tackle a lot, but this is just a taste, right? We want people to read that book of yours.

[00:28:18] Speaker A: You can go back two or three thousand years to the time of Greek and Roman antiquity, to Lucretianism and ancient atomism, which suggested that we all came about by the accidental collision of atoms, which is a particularly absurd idea. But. But it has been taken up, I will say, by such distinguished space scientist as Lawrence Krauss that you might have heard of, was on television quite a lot.

But as far as the biological dimension of things is concerned, I think Sir Charles Lyell had this idea in geology that the Earth had come about by a process which he called uniformitarianism. It's a bit of a mouthful, uniformitarianism, very, very gradually over time.

Now, Darwin, who regarded Lyell as his mentor, thought, aha, I can map Lyle's ideas directly onto the biological world.

As long as this process is glacially slow, then why not postulate that a beetle somehow became a mouse and a mouse became a porcupine, and a porcupine became a whale and the monkey became Homo sapiens and so on.

When I say it, it seems far Fetched. But that's what he thought, that uniformitarianism was the equivalent of what he dubbed natural selection.

And one can mention other people. I mean, Erasmus Darwin, who was his grandfather and even before him there were other. I mean, people talk about the preoccupation with biology of the Darwin family as a cottage industry. They were being facetious. But I mean, it was the case that over generations they were fascinated by this subject.

And so I would say that Erasmus, along with Sir Charles Lyell, was a sort of co. Equal influence upon him simply because Darwin felt. Charles Darwin felt enormous pressure to live up to his grandfather's example.

His grandfather had taken the story only up to a certain point. Point. Had no idea how things worked, only had this vague idea of transmutation of species. How do I find a way of justifying what my granddad said? Aha. This is.

Is going to be natural selection. So all those things went into the melting pot.

And as I said, as I said, the fuse minutes ago, you know, it was.

It was a sort of potpourri of different influences which made up his final thinking on these matters.

[00:32:03] Speaker B: Yeah. And he sort of adopted an approach of this is my story and I'm sticking to it. And again, I appreciate you talking about the pressures involved with Darwin.

I do know that from reading other things he had, you know, an interesting relationship with his father.

[00:32:22] Speaker A: His.

[00:32:22] Speaker B: His father in particular called him out on, you know, being lazy at school and.

[00:32:27] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:32:27] Speaker B: You know, are you going to be a disgrace to the family or are you going to get something done? You know, and things should.

[00:32:32] Speaker A: And all this he reigned him for.

[00:32:35] Speaker B: Yes, yeah, yeah. A lot of pressure to.

To perform and to offer up something that would honor the family. Exactly.

But not necessarily standing on its own scientific merit, as we've seen through the years.

Well, one of the things I enjoy about your book is that it helps to deflate the mythology surrounding Darwin that's been employed in the service of materialism. One aspect of that mythology is that Darwin's voyages on the Beagle bestowed on him the secrets of nature and were the source of his evolutionary discoveries. Gifts that later he would, like Prometheus and Greek mythology, bring to his fellow men and women and, you know, just be a gift to all of humanity.

Now, this isn't true. And it's also showing aspects of the Darwin legend that still persist. And you shed some light on that, don't you?

[00:33:32] Speaker A: Well, yes. I mean, I think that there's Darwin and then. And there's the mythologization of Darwin and that Jew must be kept asunder.

Of course, his South American voyages were absolutely formative.

They made him in so many ways. But the truth of the matter is that a number of his conclusions came to him after he had returned in the 1830s, late to 1830s and going into the 1840s, when he first had a kind of draft of thought was later to be the Origin of Species.

And yes, I mean, it would be a kind of easy mental loop for classically educated people to think, oh, well, Darwin is our equivalent, our mythical equivalent of Prometheus, or brought out fire from the gods without their permission.

But not everybody would have known of classical mythology. Only the educated elite would have. But there were other books. I mean, an article I recently submitted, and it's been published in Evolution News, concerns precursors of Darwin going back two and a half century.

Now, admittedly, these two people are fictional.

The one is Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, published in the 1590s, and the other one is Ben Jonson's the Alchemist, also published in the 1590s. In other words, around the time of Shakespeare, which was the great efflorescence of literary activity in Britain, as everybody knows.

And both Dr. Faustus, the story is that he sold his soul to the devil in order to get more knowledge about things on Earth. And the alchemist was very keen on doing all sorts of chemical experiments in order to find the elixir of life and to solve the mystery of life.

In other words, what I'm saying is that Darwin was not entirely an historical outlier.

People throughout recorded history have been interested in getting to the mysteries of existence which tantalizingly elude people.

They would literally give their soul, as in case of Faustus, in order to find out an arcane knowledge about life.

And so there are many roots that there are many sort of subconscious mental loops that people could tap into.

Funnily enough, after I'd written the article, there was a film made in 1967 starring none other than Richard Burton and Josephus Taylor called Dr. Faustus.

And when I listen to Richard Burton's rich baritone voice, he reminds me of Darwin at his most intransigent and insistent. And also a little bit of Professor Richard Dawkins at his most maniacal.

[00:37:18] Speaker B: Yeah, interesting.

[00:37:20] Speaker A: All love to know the truth of existence, myself included.

But sometimes these things are withheld from us for whatever reason.

[00:37:33] Speaker B: And what are we willing to pay as the cost for that search as well?

[00:37:39] Speaker A: That is the question. Yes, that's right.

[00:37:42] Speaker B: Well, Neil, this initial discussion sets us up nicely for another episode that will allow us to look at the cultural triumph of Darwin's theory, also some notable dissenters, and we'll look at the new scientific paradigm that challenges this materialist worldview that he built his whole theory on. So I want to thank you for your time today. Will you come back and join me one more time?

[00:38:05] Speaker A: Certainly will.

[00:38:06] Speaker B: Okay.

Well, audience, if you'd like to start reading Neil's book, in the meantime, go to Discovery Press for details and to order. That's Discovery Press. It's out and available in paperback and in digital formats now. So get yourself a copy and dive into it. And don't forget, you can watch interviews just like this one on our new YouTube channel. Subscribe today and share a video with a friend. That's at YouTube.com@idthefuture. Well, I'm Andrea Germit for ID the Future. Thanks for joining us.

[00:38:39] Speaker A: Visit us at idthefuture. Com and intelligentdesign. Org. This program is copyright Discovery Institute and recorded by its center for Science and Culture.